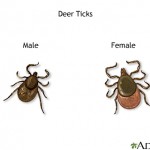

One of these Lyme Disease spreading ticks could end up on you or your pet.

This article originally appeared on Dr. Mahaney’s The Daily Vet column on petMD.

Now that you’ve gotten up to speed on the Clinical Signs, Infectious Diseases, and Natural Treatment Options for Fleas, let’s move onto the flea’s fellow blood-sucking proverbial cousin, the tick.

Tick Appropriate Environments and Situational Opportunism

Like fleas, ticks require the right combination of environmental factors to flourish: warmth, moisture, and nourishment.

Urban areas tend to be less densely concentrated with ticks as compared to suburban and rural environments, mostly due to the overall lack of foliage. Long grasses and wooded areas provide safe havens for ticks to reproduce, as well as plentiful animal hosts from which they can acquire their blood based nutrition.

Since moving to the urban jungle of Los Angeles, I rarely see ticks attached to my patients’ bodies, and infrequently attain positive diagnoses for tick borne disease. Most of my patients live a coddled, indoor existence, with most of their outdoor excursions limited to sidewalks and minuscule patches of closely-clipped lawn.

In contrast to fleas, ticks cannot jump; they instead crawl onto their host. This is unlikely to happen as your pet lounges on the carpet inside your house, but a jaunt through a grassy field or the woods permits plenty of opportunity. Ticks lurk on blades of grass or leaves and latch on to animals’ coats as they pass by. Carbon dioxide, warmth, and other chemical attractants exuded by animals and people direct ticks to their next meal.

One of these Lyme Disease spreading ticks could end up on you or your pet.

This article originally appeared on Dr. Mahaney’s The Daily Vet column on petMD.

Now that you’ve gotten up to speed on the Clinical Signs, Infectious Diseases, and Natural Treatment Options for Fleas, let’s move onto the flea’s fellow blood-sucking proverbial cousin, the tick.

Tick Appropriate Environments and Situational Opportunism

Like fleas, ticks require the right combination of environmental factors to flourish: warmth, moisture, and nourishment.

Urban areas tend to be less densely concentrated with ticks as compared to suburban and rural environments, mostly due to the overall lack of foliage. Long grasses and wooded areas provide safe havens for ticks to reproduce, as well as plentiful animal hosts from which they can acquire their blood based nutrition.

Since moving to the urban jungle of Los Angeles, I rarely see ticks attached to my patients’ bodies, and infrequently attain positive diagnoses for tick borne disease. Most of my patients live a coddled, indoor existence, with most of their outdoor excursions limited to sidewalks and minuscule patches of closely-clipped lawn.

In contrast to fleas, ticks cannot jump; they instead crawl onto their host. This is unlikely to happen as your pet lounges on the carpet inside your house, but a jaunt through a grassy field or the woods permits plenty of opportunity. Ticks lurk on blades of grass or leaves and latch on to animals’ coats as they pass by. Carbon dioxide, warmth, and other chemical attractants exuded by animals and people direct ticks to their next meal.

Tick Disease Transmission

The physical damage caused by the bite of a tick isn’t typically a life threatening concern. Yet, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health report a variety of potentially fatal diseases originating in ticks, including:- Bacteria — Anaplasmosis, Ehrhlichia, Lyme disease (Borrelia burdorferi), Mycoplasma (Haemobartonella), Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF), Tularemia (AKA "Rabbit Fever")

- Parasite — Babesia (a single celled organism, or protozoa)\

- Virus — Tick- borne encephalitis virus (TBEV, caused by a Flavivirus)

- Other — Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness (STARI, caused by an unknown agent), Tick Paralysis (caused by a neurotoxin in tick saliva)

Clinical Signs of Tick Infestation and Tick Borne Disease

Unlike fleas, you’ll likely not see your pet chewing, licking, and scratching at the site where a tick latches onto his skin. Visual inspection of your pet’s skin by separating tufts of hair and closely feeling all body parts typically permits discovery of a tick. The head, ears, neck, and limbs are common locations, as they tend to touch the grass or leaf where the tick awaits its prey. Animals having a tick borne disease can show clinical signs including (but not exclusive to):- Anorexia (decreased appetite)

- Hyperthermia (elevated body temperature)

- Joint and muscle soreness

- Lethargy or reduced mobility

- Mucous membrane pallor (pale gums)

- Tachypnea (elevated respiratory rate)